On Independence Day in America (or New Zealand’s July 5), a robotic spaceship entered the orbit of Jupiter, the solar system’s largest planet, for the first time. It took the Juno spacecraft five years to reach the distant planet, and entering its orbit came down to a 35 minute window of nerve-wracking monitoring. New Zealander Isha Welsh was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory with NASA’s scientists that day. We asked him about what it was like.

How did you get that invite?!

Welsh: Bunny [Welsh’s wife] works for this artist Doug Aitken. He met Scott Bolton, one of the primary investigators of this Juno mission at some sort of conference and they hit it off. Part of Scott’s job, as well as being a scientist on this mission, is to get knowledge of this mission out to the rest of us. He’s interested in Doug and in artists because they express abstract concepts in a physical way. That’s how we got the invite: Doug invited us. It was kind of lucky.

What, he could just bring a friend along to something like this?

Kind of! All of the people involved in the mission couldn’t control Juno at this point. It was all going automated, so they could basically just sit with their family through this really nervous time, and make sure it all went to plan. Which it did.

What was the building like?

They monitor and control Juno from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which is out in Pasadena.

The lab feels like a university campus. There’s maybe 10 or 15 quite large buildings. Some are scientific labs and clean rooms where they assemble spacecraft, and some are for monitoring. There were about 200-300 people spread through three or four rooms.

Good snacks? Was there an open bar?

There was coffee and tea and baked goods. It was like a rotary club spread.

Did you do anything to prepare?

I just read up on it quickly so I knew what I was going to see. But they totally did a background check on us. Anyone without an American passport got asked questions. I guess that’s fair enough, when you’re somewhere...governmental.

So, what was the scene like in there?

The main building we were in was the communications hub that you see on TV. It’s like rows of computers with the engineers monitoring different systems on the spacecraft. They’re basically just making sure it’s all going to plan and going ‘nominal’, as they call it.

The way they projected it mathematically is a ‘nominal’ situation, and the spacecraft is supposed to follow that nominal mathematic route -- to the inch. When that’s all happening, they’re all very, very pleased.

Were they using old, large, weird-looking computers?

No, they were just banks of what looked like PCs, just screens and keyboards, and they’re basically looking at read-outs -- complex graphs. We were in observation rooms to the side, with a bunch of screens showing what they were seeing, and some of the scientists in our room were explaining what was going on.

So you were basically watching a whole lot of people who were watching screens?

Yeah, the most interesting thing is watching the people watching the screens! I was watching the engineers, because they were the ones sweating. They’ve sent this thing out, looped it around the earth, and the rocket has to fire at exactly the right time to slow down to the right speed, and it has to be caught in the gravitational field of Jupiter, which they don’t really know too much about. Apparently there’s insane amounts of radiation around Jupiter, so they didn’t know how that would affect the spacecraft or the rocket or the readings.

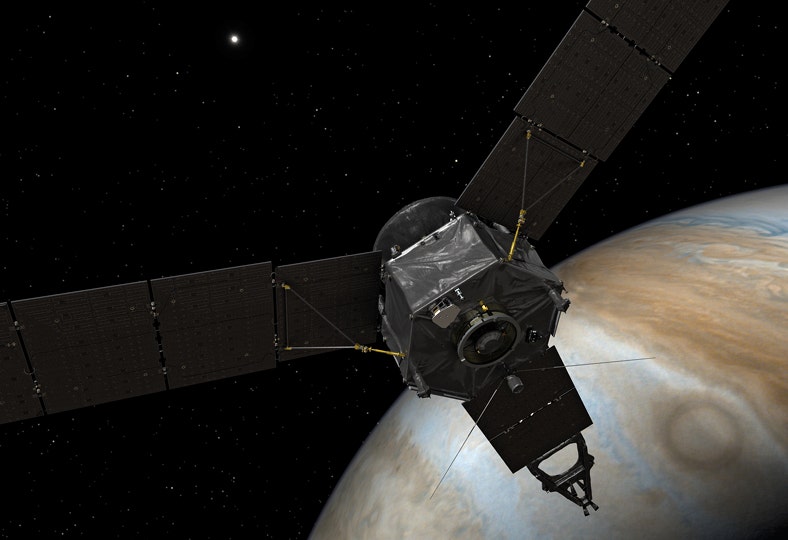

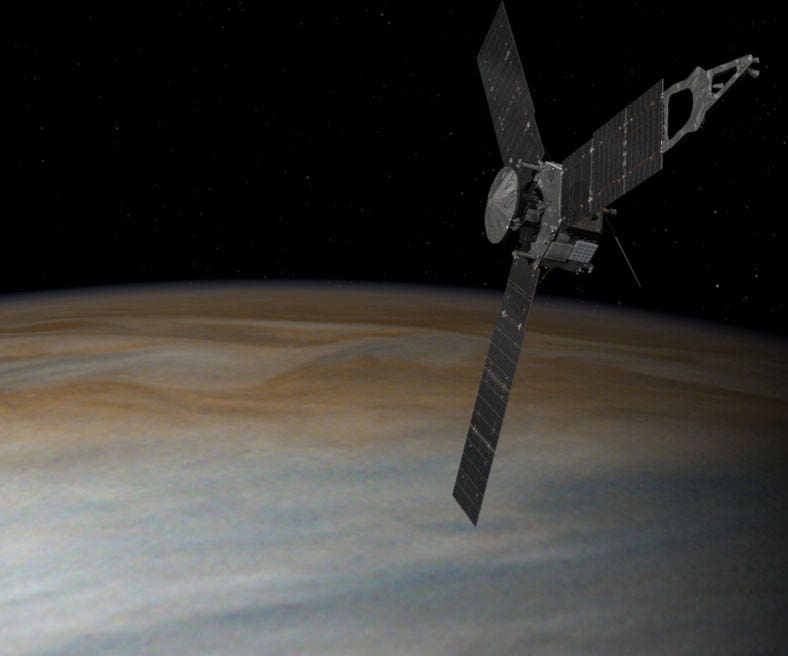

There were a whole lot of firsts for the mission, which they were already pleased about. Like, this one’s solar powered, when all of the other craft that have gone out this far have been nuclear-powered. This one’s got solar panels, but out there, there’s only one-25th of the sun’s reach that we have, so it’s getting far less sun to power the panels. The whole thing is powered by 500 watts of power. That’s like five lightbulbs to power the whole spacecraft for the entire time it’s out there. They’re just lithium ion batteries, the same as in your iPhone or whatever.

Four days out from getting to Jupiter, they powered down everything they didn’t need. The cameras were turned off. The radio communications they usually have were turned off, except for two very basic forms of communication. And they turned it away from the sun so it went dark, power-wise, and then the rocket fired for 35 minutes to slow it down, and then they had to turn it back. You could tell they were super-stressed about that whole movement happening.

That’s what we were watching. We were there for that movement, and you could tell that was the thing that was stressing them, because everything else up to that point had gone perfectly. This was the moment where, if anything happened, they’d lose the spacecraft.

Was it noisy?

It was pretty quiet. It takes 48 minutes for the radio signal to get from Juno to earth, so if the spacecraft had crashed, it would have taken us 48 minutes to realise that. So everything had actually happened already, but they were getting the radio communications back, at that point.

There were two forms of communication with this spaceship. There was a ping. So, when the spacecraft had turned around to the perfect position, it sent out a ping, like a note on a piano, and they would know from that note that the turn had reached the optimum position for firing. Then there’d be like an A note and that would be the rocket firing. So they knew from these pings that things were happening, and in the right order.

They also had this thing called a Doppler, which sounds like a steady stream of radio signal. Imagine just a big band of sound, and when that sound changes pitch or frequency, they know the spacecraft is moving or slowing down, so they can tell that in real time.

What did the pings sound like?

Just like something on your phone. Like getting a text message or something.

I love some of the imagery shared by NASA. Artist’s renderings of space missions can be very awe-inspiring to look at, even if they’re artist’s renderings and not the real thing.

They showed what looked like a really fuzzy iPhone video taken from a mile away, of Jupiter, which was a white dot about the size of a marble, and then all these other little white dots, which were its moons. It was the first live video footage they’ve ever seen of that. So they’ve got bad grainy footage of how these moons move around it.

Yeah, that footage was disappointing. I was really hoping to see something that looked really high def, like the images you see of Earth.

That’s all come from the Hubble telescope, mainly. The ones from Juno seem to be not high res -- they’re really after microwave readings.

But I guess that’s part of their challenge: how do they transfer some of that knowledge to the rest of us, without making it a fiction? We don’t want a Weta rendering of it. We don’t want a CGI universe, but we do want something to understand, otherwise it’s just pages of numbers.

They also want us to be along on this journey. I got the feeling they want young scientists to enter the field, which they’re probably not as much anymore. People are going to business school. They want to be hedge funders; they don’t want to be JPL scientists. Which is a problem.

There was a tonne of young people there and the excitement was real. So that was a really smart thing to do. I think it was half outreach and half let’s-watch-what’s-happening. Both are really important.

When they did the last Large Hadron Collider run and they were going to prove the Higgs Boson theory, I livestreamed it at home. I knew it was a big deal and had taken a long time and cost a lot of money and that a lot of people from a lot of countries were involved, and I could see how excited they were. I only had a vague grasp of what was going on, but it was still very emotional to watch all those people’s lives coming to that point.

It was the same thing here. There were rounds of applause, people were visibly excited when good things happened, and it finally just slotted into orbit.

When they announced the finish of the burn and it was clear that everything had gone better than well, I was totally choked up. Sending something that far, slingshotting it around Earth... it ended up being the fastest man-made object ever made. It goes 160,000 miles per hour, 25 miles every second.

And then it ends up entering orbit on Independence Day? There is that totally patriotic thing of “we’re just the greatest team on earth!” Maybe I’ve been here too long, but I don’t find that gross. It was actually a really nice moment. It was a big team effort, they’d just achieved something, and that was the vibe.

And it’s the search for knowledge! I think we all get involved in that, in some way or another. I mean, we can talk about this spacecraft and what it was doing, but why it’s out there…

Apparently, Jupiter is most like the sun, out of anything. It’s also one of the only planets that gives off more energy than it takes in. So, it’s emitting heat and radiation this whole time, just like the sun does, but it gives off more energy than the sun gives it. So it’s still burning up, it’s still active, in a sense. They don’t understand it.

They think it’s made up of a liquid metallic hydrogen. The hydrogen in it is so compressed, it’s under such great forces, that it turns metallic. Which I don’t even understand.

They think it was around and very important in the formation of our solar system, which they want to know more about. And that’s why this thing is out there. That’s slightly more daunting (to me, anyway) than the engineering of the spacecraft.

The scientists want to know some pretty important stuff, I guess. The moons around Jupiter apparently have an ice cover and they suspect there are water oceans underneath the ice. So, it’s probably the biggest source of water outside of earth, anywhere else in our system. They’re gonna crash Juno into Jupiter after it’s finished, so it doesn’t contaminate or affect these moons, in case there is some sort of ...residue of life...or life...or cellular...anything! It’s like understanding human history but it’s pre-human history.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/24/doug-aitken-non-stop-art-barbican-takeover-station-to-station