Standfirst: A documentary at the Resene Architecture and Design Film Festival celebrates the ineffable beauty of a disappearing artform.

There are some mournful statistics disclosed towards the end of Neon, a painstakingly assembled film by Australian documentary-maker Lawrence Johnston, currently touring the country with the Resene Architecture and Design Film Festival.

Of the hundreds of thousands of neon signs that lit up Manhattan from 1900 to 1960, only a few hundred are left. In 2009, a photography book carefully documented all the homely neon signs illuminating small New York shop fronts. Two-thirds have now gone. Like acres of Amazonian rainforest, they’re disappearing for good.

What was a symbol of modernity and prosperity at the beginning of the 20th century took a swift slide into decrepitude by the end of World War 2. Few shop owners now choose to repair their flickering and fizzling neon signs, when they could just get a cheaper LED sign instead.

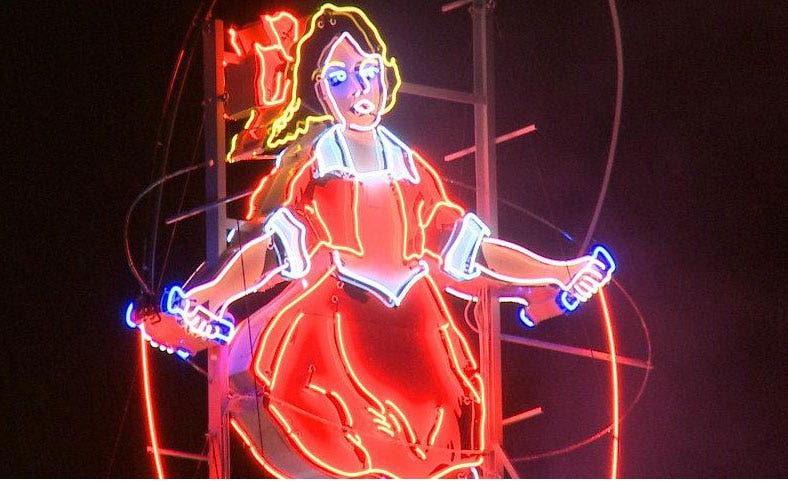

Why would anyone want to watch a whole movie about neon? Neon cuts together archival footage of the world’s most impressive neon articulations with interviews with enthusiasts who love neon so much they grow dewy-eyed when talking about its beauty. Pretty soon, you come to feel some of what they’re feeling.

Neon has its own ineffable charm. “People can sense that something’s buzzing!” someone says, summing up neon’s sense of hyper-activity. Walk past a huge neon sign and you’ll know that something’s up - or once was.

Johnston’s documentary is in some ways the history of how something totally hip and desirable can become so unwanted so soon.

It begins with incredible archival film footage from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, showing large stone state buildings miraculously lit up by gleaming, assertive neon bulbs for the first time.

Originally, neon was a sign that your business was as modern as can be. Georges Claude, a French engineer, figured out the industrial applications of liquefying air in 1902, and demonstrated one byproduct - “glow discharge” tubes - at the 1910 Paris Motor Show. He held the patent for neon signs for years and grew rich off the profits.

Las Vegas became ‘an electric bath’, the site of a sort-of arms race to build the biggest and brightest sign.

The possibilities of neon were endless, and signs were often created by tipsy salesmen who would negotiate crazy designs on the back of a cocktail napkin, then hand the project over to engineers to attempt to build.

One of the greatest examples was the Stardust Casino, a hotel on the Strip that was demolished in 2007. Its sign used more than 2km of neon tubes to represent our solar system, with the hotel’s name rendered in a classic old-school ‘Googie’ font, amidst constellations of starbursts, rings and rays. In 1951, a 12m high cowboy, “Vegas Vic” was erected on The Pioneer Club. He smokes a cigarette, waves his arm and every 15 minutes says, “Howdy Podner!”

The film also tours the rest of the world, pausing in London, Hong Kong, Havana, Shanghai and even Sydney, and stopping to admire Osaka’s next-level neon signs with complex animations.

In 1930s films, montages of gleaming neon nightclub signs promise giddy fun, sex, dancing, affluence. But neon’s associations with sleek futurism and affluence had sloughed off after a few decades. The upkeep on neon can be expensive - so people grew used to seeing once-beautiful signs missing bulbs or not lit at all.

By the late 1940s, neon had become synonymous with sleaze. “The joint looked like trouble,” film voiceovers would say, as the camera panned across a flickering, broken neon sign. In It’s A Wonderful Life, Jimmy Stewart runs through an alternate version of his friendly hometown, now cruelly ravaged by brassy neon signs for cocktail clubs and casinos.

It became good form to rip down your old neon and replace it with less fragile, cheaper plastic signage.

It took until the late 70s and early 80s for people to care about preserving neon, out of respect for its artistry. It’s been made the same way for 100 years, every tube made by hand, blown and shaped by skilled neon benders.

In 1987, some saviours began turning LA’s long-dead neon building-top signs back on, as part of a restoration project that has cost around US$350,000. Passing the iconic El Royale apartments, a little old lady said to a crew member, “You’re fixing that green sign?” The building’s pistachio green crown had been turned off for 50 years, but clearly its imagery had that kind of staying power.

To find Neon screenings near you,

visit www.resene.co.nz/filmfestival