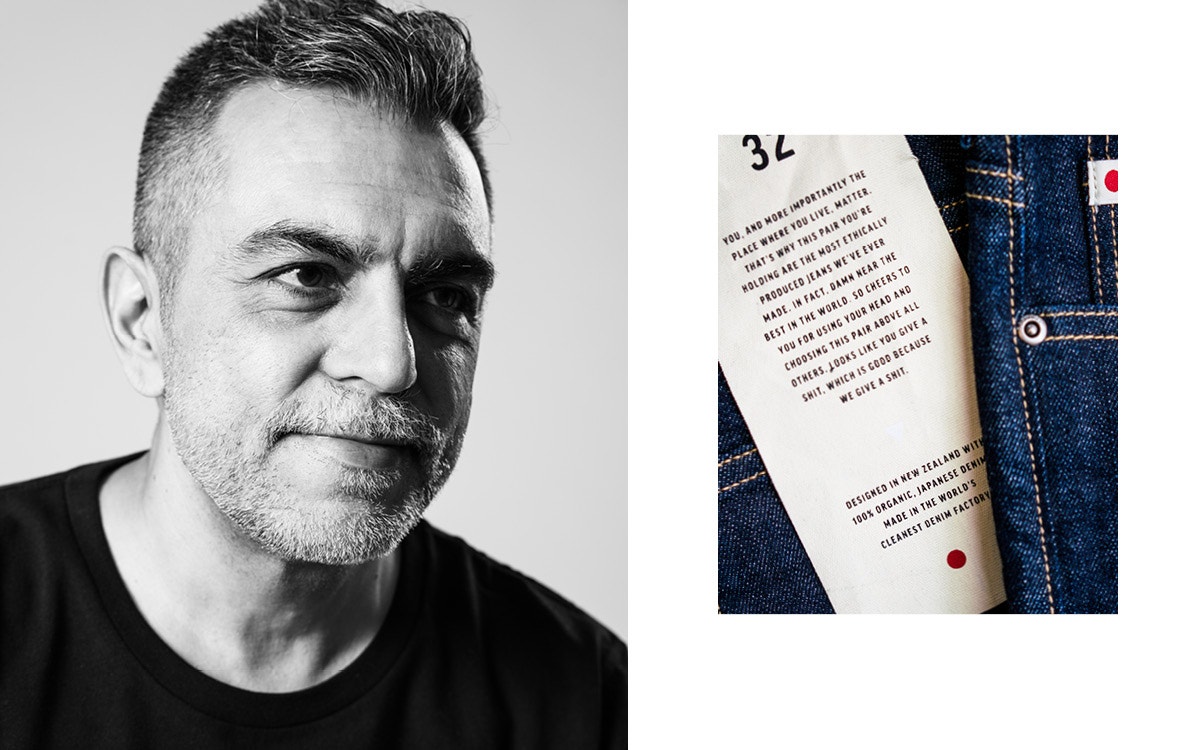

Half an hour from the centre of Ho Chi Minh, the redemption of denim is underway. Don Rowe visits Sanjeev Bahl, founder of the cleanest denim factory in the world, and learns why Barkers have partnered with a true fashion maverick.

It took Saitex denim founder Sanjeev Bahl nine countries to settle on Vietnam. From Egypt to Mauritius, Sri Lanka to Bangladesh, Bahl saw again and again the environmental and human devastation of the apparel industry. He vowed to do better.

“Through my travels I could see modern day slavery,” he says in his office in Ho Chi Minh. “Through my travels I saw abject poverty, inequality, mental damage, inadequate sanitation – it’s all bad. I didn’t want to participate in that economy.”

Internationally there is no common law on how a factory should look. And, because of the transitory nature of the industry – where businesses move entire continents as laws and costs allow – very little investment is made in people or the factories. Inevitably, this leads to disasters like the Rana Plaza tragedy, where workers are crushed as shoddily built factories collapse around them.

“What was always in my mind was that when we build our own factory, we build it the opposite of what I’d seen,” says Bahl. “That was the real reason to do things right, and not to continue on that path of destruction. That was the mantra.”

Thirty kilometres outside the CBD, the Saitex factory bills itself as the cleanest denim factory in the world. Four and half thousand employees work here, turning raw Japanese denim into sustainable clothing for brands determined to make a difference to the environmental and social cost of their garments.

Fast fashion notoriously takes a severe toll on both the environment and the droves of workers bent over their machines, spray guns and washers. Names like Rana Plaza are synonymous with the deaths of thousands of employees burned, crushed and poisoned. Luckier workers face a continually decreasing quality of life, as their mental and physical health deteriorates under the harsh factory lights.

Denim production is particularly problematic. In denim-producing nations like China, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, toxic indigo sludge chokes the life from rivers and streams, hastening our worldwide environmental destruction.

But at Saitex, the denim sludge is filtered out and mixed with cement to create bricks, with which Saitex has built four orphanages. Ninety-eight per cent of the water is recycled, the drinkable product funnelled back into the space age laundry which utilises vertical washers, ozone technology and lasers to finish jeans. It’s not only right, but profitable too.

“What we started looking at was what was beyond cost. With everything that you make, there is waste,” says Bahl.

“We started looking at every possible form of waste we generate, and how could we turn it into a profit. Our investments into recycling, they paid themselves off in less than six years. We made money on it. And then of course with energy, our strategies are also profitable. There again we broke even in six years.”

The profits have funded the rollout of an electric moped programme, which aims to replace the 4,500 bikes at Saitex with electric alternatives. The initiative both saves employees money on petrol and reduces the factory’s carbon footprint by 18% – making their ambitious goal to be carbon neutral by 2023 one step closer. Elsewhere, Saitex used denim scraps in a partnership with Puma to create a line of shoes which raised upwards of $350,000, funding the construction of another orphanage.

But Bahl’s motivations go beyond the material. A devotee of Sai Baba, a 19th-century religious teacher, Bahl is a studious meditator and says his practice has informed every facet of the factory – itself named after Sai Baba.

“I think we feel as a human, we are all so bottled up in our own countries and our own boundaries and it’s all about our own comfort. We rarely look outside and see how much suffering there is on this planet.”

In Bahl’s office is a framed copy of the New York Times from October 28, 2018. Tiny Yemeni girl Amal Hussain lies emaciated, her face turned away, a tragic innocent during a time of war. He keeps the photo as a reminder and as a motivator to push Saitex further and to use that momentum to affect real, impactful change.

“Human beings and their ideologies, everybody has their point of view which scales up into conflict, but when people get into conflict they don’t realise the pain that they create all around them. It was really difficult but I decided to frame it and keep it so that it reminds me every single day that we have a broader and larger vision.”

In a shipping container across the street, a row of basil plants hung vertically from the ceiling reflects the blue and red glow of hundreds of LED lights. It’s cool inside. There is refrigeration and even speakers. This one scalable box can grow as much food as three acres would outside. The plan is to distribute the produce to the orphans cared for by Saitex. It’s a solution – maybe – to one of Bahl’s obsessions: the scarcity of food and water worldwide.

“I think food is really, really important. Food and water. I would not like to see in anybody’s lifetime wars being fought over food and water. I’m always looking at 2050, and I keep on asking myself, I keep painting a picture of how this planet will look – you don’t have to be a nuclear scientist to figure that out.”

In a frequently exploitative industry, one which looks only to the nearest of futures, where workers are used and exposed, Bahl is a maverick. And with partnerships ranging from Calvin Klein to Barkers, he’s showing it’s not only possible to do the right thing, but profitable too. As Vietnam booms and a new age of consumerism begins worldwide, Saitex is leading the way in ethical and sustainable business.