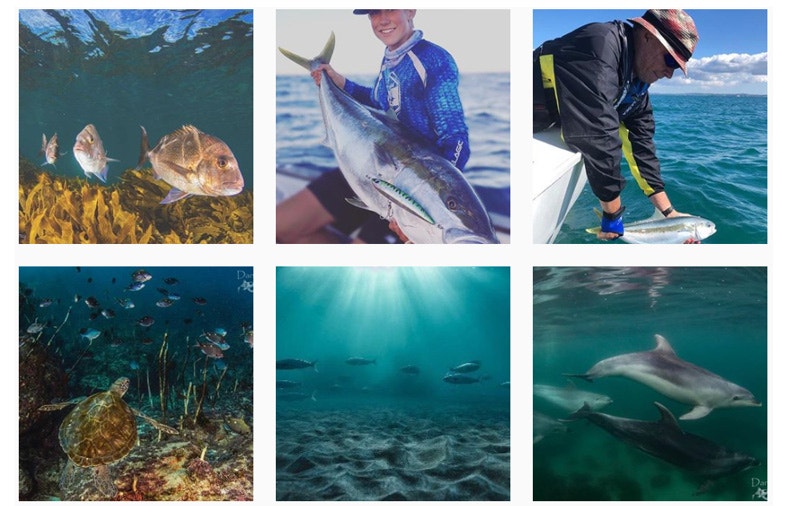

Our oceans are under pressure. Environmental degradation, climate change and poor commercial fishing practices continue to put huge pressure on the ecosystems beneath the water. Now is the time for change.

A lot of Sam Woolford’s earliest memories take place on the ocean fishing and diving with his dad. But he worries if current destructive fishing methods continue, future generations won’t be able to experience the same thing. This why he chucked in his corporate office job to be the Programme Lead for LegaSea.

LegaSea raises awareness and advocates for the restoration of our coastal fisheries. When we meet at the Outboard Boat Club on Tamaki Drive, he’s quick to launch into his fears for the future of our marine ecosystems.

“Crayfish are now considered ‘functionally extinct’ in the Hauraki Gulf. Tarakihi stocks along the entire East Coast of New Zealand are at 17% of their original biomass. There’s a whole lot of fish populations in real trouble, we can’t continue to push these ecosystems to the edge. One major event, be it el nino or global warming and the result could see a complete collapse.”

We were talking about a bit of news that came up recently – a review of the rules governing the commercial industry. One of the proposals in particular has caught the attention of LegaSea – that to prevent dumping at sea, everything caught by a commercial fishing vessel has to be brought to land. LegaSea is against the proposal because it doesn’t address the way in which the fish are harvested and it won’t do anything to prevent damage being done to fish stocks and ocean ecosystems. Woolford goes through the technicalities with the tone of someone getting steadily more exasperated, as if every time he has to explain it he realises again why he doesn’t like the idea.

“Yes, the commercial industry is killing a lot of fish needlessly at the moment, but legitimising that isn’t the solution. If you want to minimise the impact on the environment, don’t kill as many fish!”

Then he’s onto bottom trawling and how it “crushes all the crustaceans and rips out all the seaweed. It’s not that he is against commercial fishing, it’s the technique.

He’s seen the horrifying plastic pollution that has started to fill the oceans over the course of his life too, saying it “does my head in.”

There’s a reason why Woolford sounds so passionate about the ocean – he’s lived pretty much his entire life in love with it. He grew up around the Manukau Harbour, taking spinners down to Blockhouse Bay in search of kahawai on Saturday mornings. Part of it was about getting some fish to eat, and part of it was just about experiencing beautiful days on the ocean.

“It never got old – that’s just what we used to do as kids.” He trained first as a diver, and while that remains his main passion, there was a period in the middle when he worked as an accountant and a marketer. Now he’s involved in something he considers much bigger than himself.

Woolford has kids of his own now – two daughters aged four and six. They’re already coming out on the boat with him, the elder one caught her first legal snapper at the age of three. He’s teaching her how to snorkel at the moment, “because I need a dive buddy.”

It personalises LegaSea’s mission of making sure the oceans are still alive for future generations – he’s adamant his kids, and their kids, have the same opportunities to experience the ocean he had growing up.

The reason he invited me down to the Outboard Boating Club is to show me an innocuous looking shed, which houses a remarkable, culture changing operation. It’s a filleting shed, where OBC members can bring fish they’ve caught, and get the fish filleted by a professional fish filleter. Normally, the fish head and the frame then just get chucked out. But no more.

The Kai Ika Project brings together The Outboard Boating Club, Papatuanuku Kokiri Marae in South Auckland and LegaSea. OBC members collect the fish parts and marae volunteers take the fish heads and frames to the marae, where they’re distributed to the community. After all, in multicultural Auckland, there are many people who say that’s the best bit of the fish. Some Māori consider it to be ‘rangatira kai’ – food fit for a chief. There is only one head of the fish, after all. It can be used in all sorts of ways, too – curries, chowders, fish stock.

The project has been remarkably popular – more than 31,000kgs worth of fish parts have been repurposed since they started. The whole fish is used too, with the offal used as part of a fertiliser to grow kumara. The idea of ‘complete utilisation’ is starting to take off. This means fewer fish need to be taken out of the ocean – a vital development towards becoming more of a true sustainable fishing country which we certainly aren’t now.

But the thing about generational change and learning is it doesn’t have to just go one way. Woolford tells a story about seeing his dad catching up with a mate, and his dad needing to tell his mate all about how he had made an amazing smoked fish stock with a fish frame, so another meal could be made from the one fish. And by the sound of it, the second meal was even better than the first.

As far as Woolford sees it, these are the sort of changes that need to be made in how everyone treats the ocean. It has given him so much joy in his life, and he wants others to experience the same thing.

“If you want to see future generations go out and enjoy kaimoana, to go out fishing and have these experiences, we’ve all got to do something.”

Images from Sam Woolford and LegaSea.