There are books you flick through, forget, and consign to the KonMari pile. There are books you finish and never think of again. Then there are the classics: those stories that stick in the subconscious and that are capable, decades later, of transporting a reader back to the boy he was when he discovered them.

Here are our top five childhood classics – stack ‘em up and brace for a wallop of nostalgia.

1. White Fang

A wolf pack stalks two men and their dog team in the freezing forests of Canada. The pack is starving. They pick their prey off one by one.

The desperate precision of those wolves, the way they come in the night, man’s pitiful shreds of fire up against the vast, primal dark – this section remains one of the most terrifying in children’s literature. (Well, it wasn’t exactly written for children, but it is beloved of them.)

The rest of Jack London’s 1906 masterpiece follows the fortunes of a cub of one of those wolves and it’s hardly short on violence. We get she-wolf versus lynx, wolf versus fighting dogs, wolf versus men, repeatedly. White Fang is shaped by injustice and torment. Yet there’s a profound sort of peace, too, in London’s imagining of the lupine mind.

The aim of life was meat. Life itself was meat. Life lived on life. There were the eaters and the eaten. The law was: EAT OR BE EATEN. He did not formulate the law in clear, set terms and moralize about it. He did not even think the law; he merely lived the law without thinking about it at all.

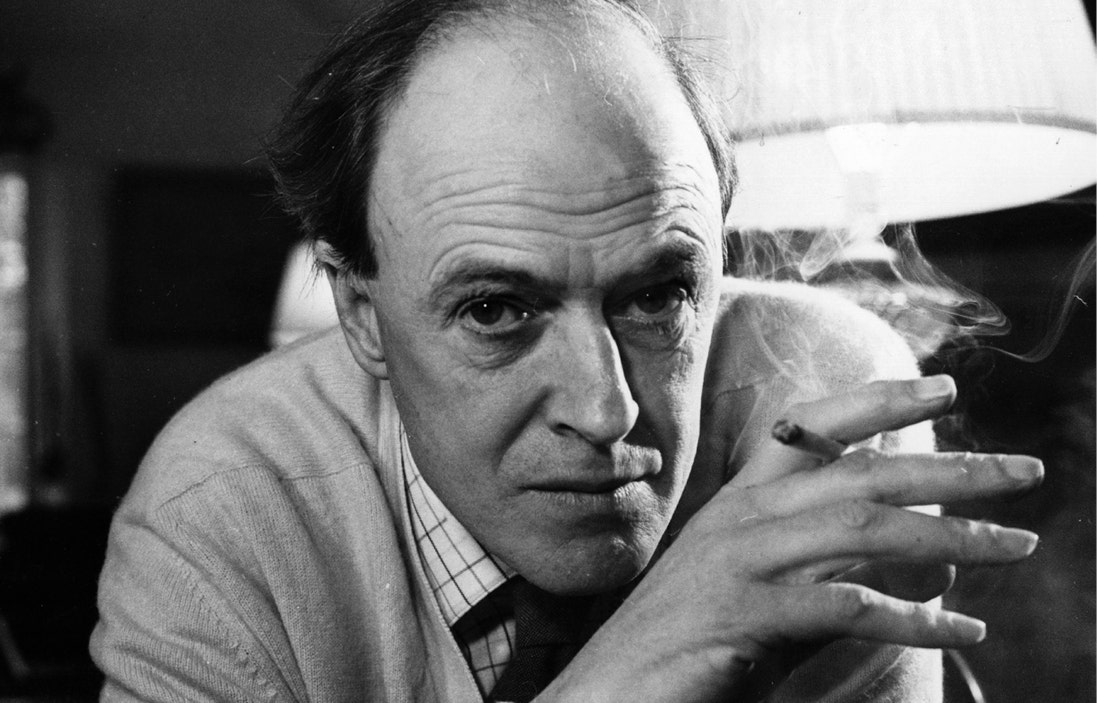

2. Going Solo

Roald Dahl was definitely an asshole at times, and sure, he might have taken liberties with the detail of his years as an RAF pilot but c’mon. Man’s a legend. And whether this second part of his autobiography (see Boy for his horror stories of boarding school) is fantasy or fastidious truth, Going Solo is pretty legendary too. Stand-outs include this description of a dogfight in the skies above Athens:

Suddenly the whole sky around us seemed to explode with German fighters. They came down on us from high above, not only 109s but also the twin-engined 110s. Watchers on the ground say that there cannot have been fewer than 200 of them around us that morning...

They came from above and they came from behind and they made frontal attacks from dead ahead, and I threw my Hurricane around as best I could and whenever a Hun came into my sights, I pressed the button...

The sky was so full of aircraft that half my time was spent in actually avoiding collisions. I am quite sure that the German planes must have often got in each other’s way because there were so many of them, and that probably saved quite a number of our skins.

I remember walking over to the little wooden Operations Room to report my return and as I made my way slowly across the grass I suddenly realized that the whole of my body and all my clothes were dripping with sweat.

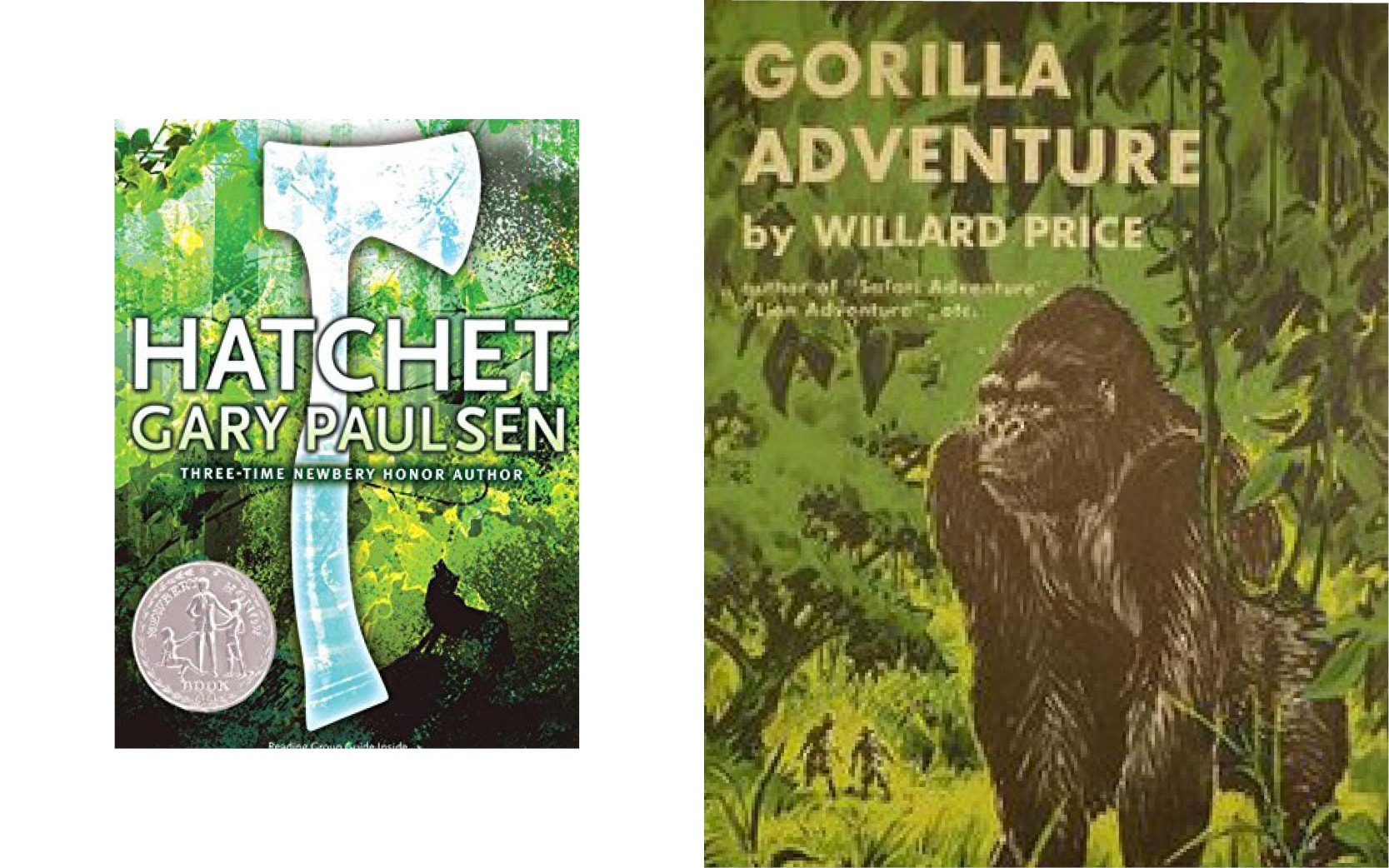

3. The Willard Price Adventure series

Big brother Hal is still an insufferable bore. Little brother Roger is still an insufferable naif. And yes, 50-odd years on, the premise of their adventures is problematic – the teenage brothers travel the world collecting animals for their father’s wildlife park. There’s an uncomfortable dose of colonialism, too: see Cannibal Adventure, set in New Guinea circa 1972.’

But. There are 14 of these books, each packed with true facts and with something super-cool on the cover. An erupting volcano, or a huge shark, or a river of crocs. And every time the plot is basically ‘awesome animal encounter after awesome animal encounter’. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of the cast of Gorilla Adventure, for example: an angry silverback, a honey badger, a bunch of elephants and baboons, a giant albino python that wrestles a gorilla, a green mamba that attacks a Land Rover, a spitting cobra and a snake with two heads. Oh, and there’s a bit where Hal’s stuck in a pit and a gorilla pushes a black leopard in to kill him.

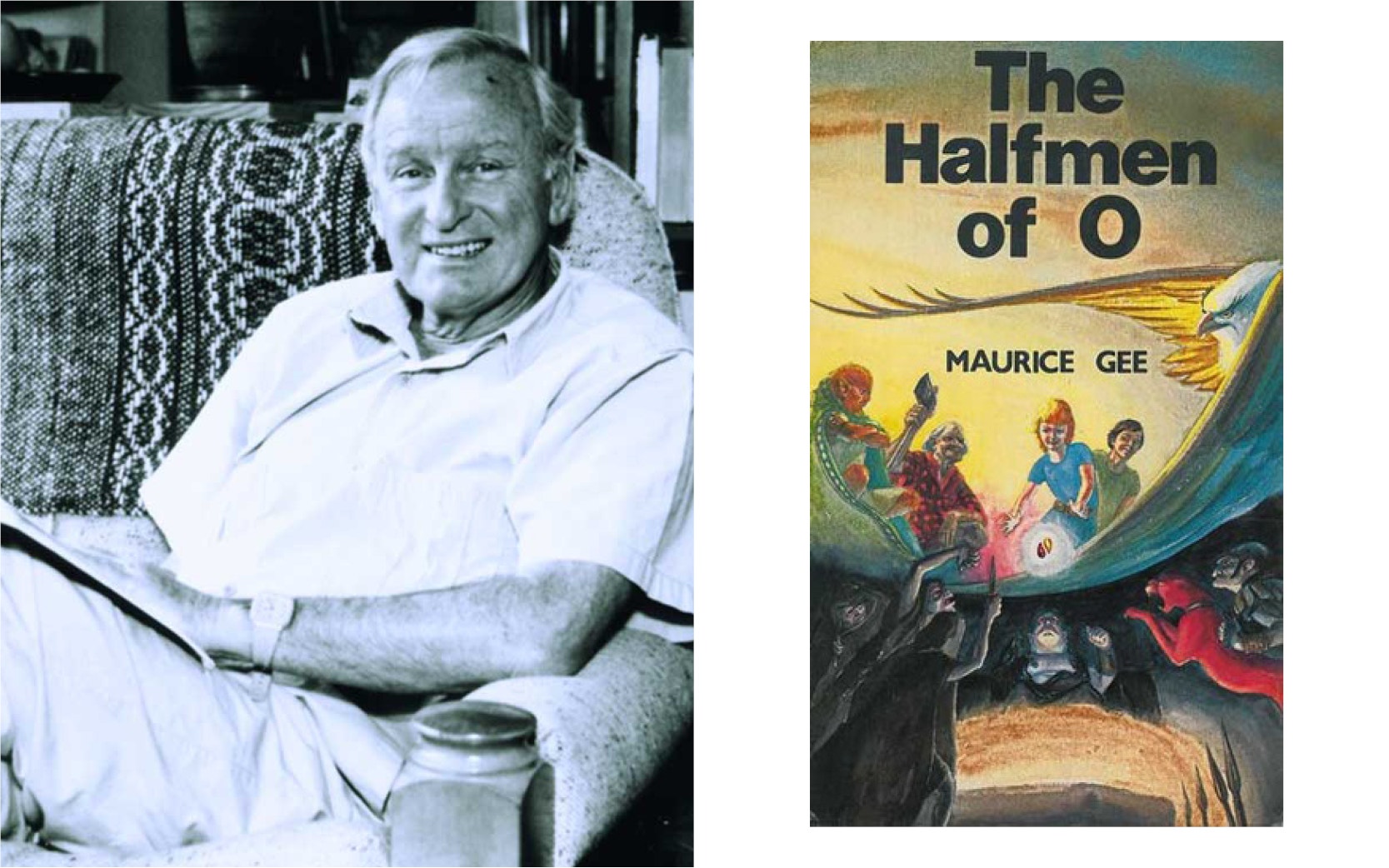

4. The O trilogy

Crimson and cruel, with an appalling scream, bloodcats are the most bad-ass creatures in all of New Zealand fiction. And they’re just one of the many, many reasons to love Maurice Gee’s fantasy series, written in 1980’s Henderson and set in a world called O.

The set-up is overtly – verging on cheesily – good versus evil, but Gee’s end-game is wholeness, finding a balance.

Here’s the thing: even a very young reader will sense from page one they’re in the hands of a distinguished storyteller. Gee’s writing is clean and evocative, his pacing bang-on, and his characterisation hitches the reader securely into the minds of the young protagonists.

The trilogy has been described as a stepping stone to Tolkien and Gee’s character names are certainly on par with the master. Odo Cling. Otis Claw. Brand, Breeze and Brightfeather. Pick the baddies.

Above all, what these stories do is plant a seed. Imagine, you think. Imagine if it was me that stumbled into O.

5. Hatchet

Things take time in Gary Paulsen’s 1987 story of survival in the wilderness. Everything takes bloody ages, actually, and as a kid reading this you think, well yes, that’s right, of course it would. You think: I’m being told the truth. Here, for example, is our 13 year-old hero Brian making fire:

There had to be a soft and incredibly fine nest for the sparks. I must make a home for the sparks, he thought. A perfect home or they won’t stay, they won’t make fire. He started ripping the bark, using his fingernails at first, and when that didn’t work he used the sharp edge of the hatchet, cutting the bark in thin slivers, hairs so fine they were almost not there. It was painstaking work, slow work, and he stayed with it for over two hours. Twice he stopped for a handful of berries and once to go to the lake for a drink. Then back to work, the sun on his back, until at last he had a ball of fluff as big as a grapefruit—dry birchbark fluff.”

All the best man-alone stories involve a fair amount of self-reflection and Hatchet delivers in spades. Brian is a thoughtful kid and his summer alone turns him in on himself. He muses on the nature of patience, of hope, of self-pity and loneliness and the imagination. And, of course, he triumphs.