Think about the history of surfing and you’re likely to picture Hawaiian kings, toes on the nose of a majestic longboard shaped from a single tree, gliding along beneath live volcanoes in front of a white sand beach. You wouldn’t be wrong. But the Hawaiian people weren’t the only Pacifica keen to shred the gnar. Maori liked it too, catching the whitewater in waka, wooden boards called kopapa and bags of kelp (poha). They also bodysurfed.

But as usual, when missionaries arrived in New Zealand and the wider Pacific, they strongly condemned anything fun, exciting or otherwise outside the norm. Apparently God was a real bore, and found the idea of his creations frolicking around in the surf half-naked quite indecent.

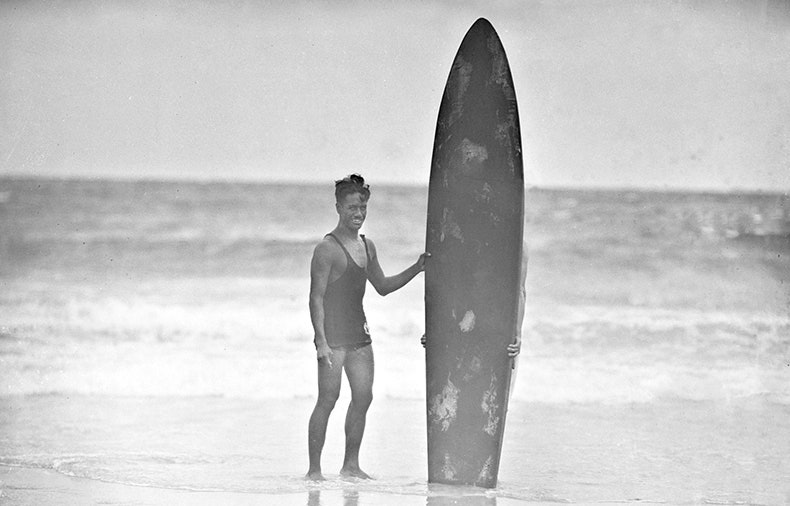

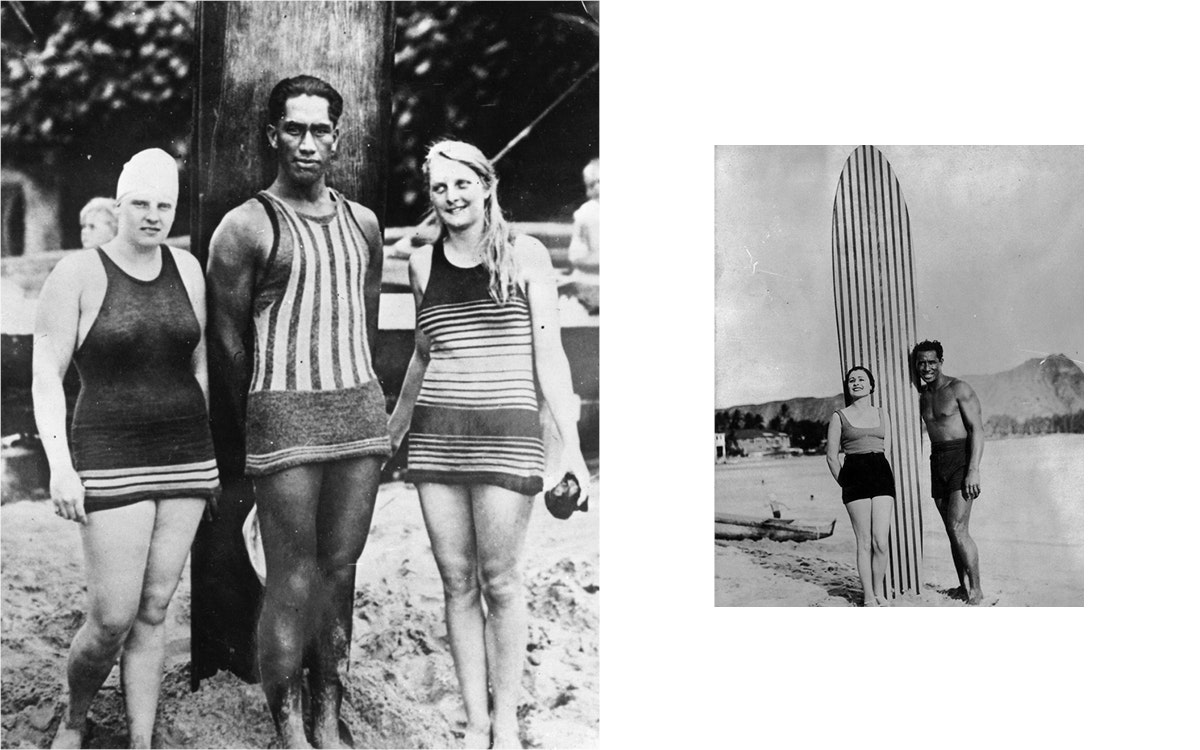

Like many of the cultural taonga that have survived religious purges worldwide however, persisted for many years on the verge of total eradication, mostly in Hawaii. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that the sport was exported to the mainland, introduced in 1906 by half-Hawaiian swim instructor George Freeth, and popularised by Duke Kahanamoku, an olympic swim champion.

In the early days of WW1 Kahanamoku brought the sport to New Zealand. In town as part of a swimming tour, it was nevertheless Kahanamoku’s shredding that impressed the locals at Wellington’s Lyall Bay. On a Sunday afternoon in March, thousands of Wellingtonians trudged up the beach to catch a glimpse of the now-immortalised Hawaiian.

“The visitor entertained them with a truly wonderful display of shooting the breakers, which, after the spell of southerly weather, were fairly large,” reported Kiwi battlers The Evening Post. “His renowned standing shoot on the surfboard was the particular feature.

"He stood right up on the board, while the latter shot along at a great speed. By careful steering he prolonged the shoot for a distance of 150 to 200 yards.”

Stand-up surfing would still remain an eccentricity for at least another 50 years, however. While in California an entire social movement and lifestyle was growing around the sport, Kiwi’s were paddling about on Surf Lifesaving longboards. Primarily for rescuing drowning bathers, the longboards were closer to small boats, or if you’re generous modern day stand-up paddleboards. But change, like swell, was just over the horizon.

As anyone who’s seen a Rip Curl poster could tell you, surfing is all about the search. While there are obviously heavy elements of fierce localism in the sport, surfing and travel go together like exotic drug use and travel. Waves, believe it or not, form basically anywhere there’s water and a change in gradient on the seafloor. Even today in a time where near every corner of the globe has been trodden and mapped, surfers pore over weather charts and satellite imagery and basically everything but a ouija board to divine the location of the next break. Surfers push themselves to the furthest locales, enduring conditions far beyond the average tourist, because they’re driven by a higher purpose.

Perhaps the most famous is Mike Boyum, a mysterious and mythical figure from the early days of surfing. A drug smuggling, sword fighting, intrepid adventurer, Boyum popularised the art of journeying deep past the pale, living on beaches surrounded by Sumatran tigers, fasting for days and subsisting on diets heavy in magic mushrooms, all in service of the wave. He’s rumored to be still living in the jungles of Southeast Asia, hiding out after stealing more than $1 million from the Maui mafia. Other reports have him dead of starvation after fasting a little too long.

But is was two other American surfers who brought modern surfing to New Zealand on on a tour of the Pacific - maybe not exactly Timor-Leste, but still a remote location at that point. A pair of lifeguards from California, their fiberglass malibu longboards were unprecedented in New Zealand, allowing them to surf across the face of the wave. After a demonstration at Piha, surfing began it’s climb atop sports in this country.

Less than 15 years later and the first national surf championships were held at Mount Maunganui in conjunction with the birth of The New Zealand Surf Riders Association, now known as Surfing New Zealand. By 1965 New Zealand had its own surf magazine and the movement became undeniable. Just as near everywhere else in the Western world, the 1960s were a time of cultural revolution. Even in Godzone, the youth were tuning in, turning on and dropping out - many of them to spend their days chasing the swell around New Zealand’s still uncrowded breaks.

Over the next few decades the boards got shorter, the hair got longer, and surfers began to congregate in certain areas, helping to spawn now world-famous towns like Raglan and Gisborne. The lifestyle was not always conducive to hard industry, but nevertheless small economies sprung up around the sport too. People like Raglan icon Mickey T, and Barkers collaborator Roger Hall, alongside a host of other shapers, built lives around their craft, these days selling and exporting custom boards for considerable amounts of money.

There became opportunities for cash too in the professional ranks. Endorsements with everyone from Red Bull through Oakley and even Coca Cola brought the corporate dollar flooding into the sport as competition circuits developed and matured across the country. Competitive surfer’s rashguards started to look a little more like Nascar uniforms and it became possible to spend a career competing against the best in the world.

These days professional surfers are cultivated from a young age, entering academies in places like Raglan and Whangamata, paddling out almost daily into some of the most consistent surf on earth. Figures like Billy Stairmand, Ricardo Christie and Paige Hareb deliver results time and again on the world stage, and travellers continue to pour into the country, now considered one of the Mecca’s of the sport.

And surfing itself is not only for the long of hair and short of cash. Everyone from builders to bankers are out in the line-up, bringing the sport firmly into the mainstream, and pushing the keenest adventurers that little bit harder.